Notions of Identity in Decentralized Systems

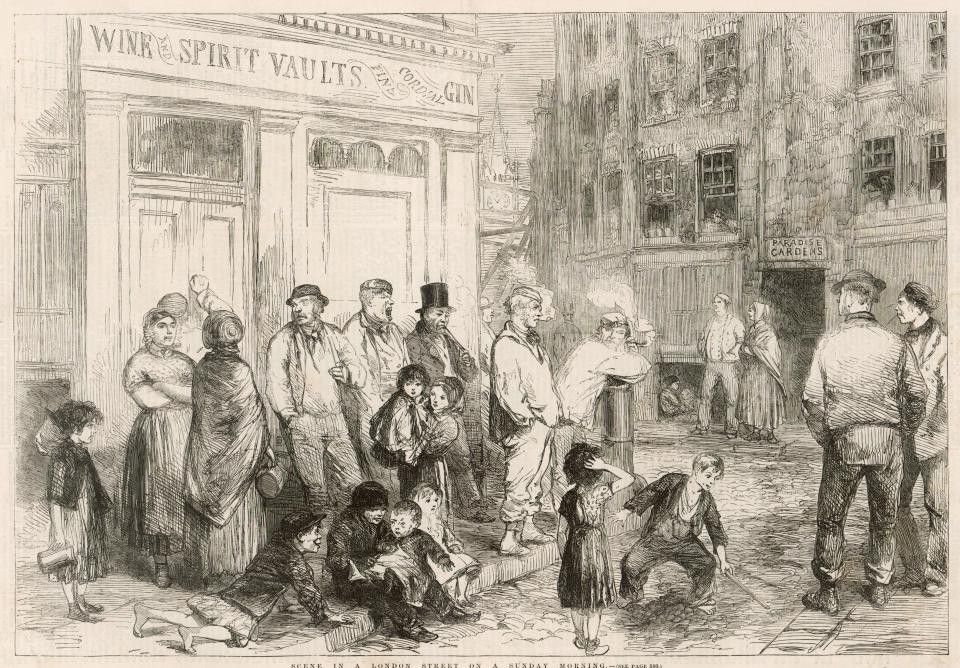

In the early 1800’s in London, there was a group of shopkeepers — tailors, haberdashers, cobblers — who periodically convened at the British Coffee House in Charing Cross. Over their pints and their cups of tea, they would discuss their customers.

London at the time, as the capital of the British Empire, was exploding with activity. This dynamic was leading to unprecedented prosperity for some of London’s residents, but it was posing a new challenge for the tradesmen who came together in that damp coffee house.

A few decades prior, all business had been local. The tailor over in Mayfair, for example, would have been serving the same customers for years. He would have known and trusted his customers, meaning he could do advance work for them and extend them credit — core pieces of how his business operated. His customers, for their part, knew they would damage their reputations if they did not hold up their side of the deal.

As London grew to be the capital of global commerce, however, the tailor’s customer base expanded. Gradually he found he didn’t know all, or even many, of the people walking through his door. Knowing who to trust was becoming an issue.

And so this group of shopkeepers was not assembled just to gossip about their customers… they came together to share names and details and, in particular, tell each other who to watch out for. Who were the fraudsters, the sharpers, the swindlers? This group called themselves the Mutual Communication Society.

Credit: A Different Type of Double-Spend Problem

Merchants’ concerns around fraud will sound familiar to anyone who has read the Bitcoin whitepaper.

Merchants must be wary of their customers, hassling them for more information than they would otherwise need. A certain percentage of fraud is accepted as unavoidable.

— Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin Whitepaper

Satoshi, in his design of bitcoin, is addressing a problem of credit. Prior to bitcoin, merchants transacting with customers over the internet had to extend credit, trusting that their customers were good for the money and would follow through in paying. Generally, merchants relied on a series of expensive and time-consuming hops through banks and intermediaries to manage their risk. “These costs and payment uncertainties can be avoided in person by using physical currency,” Satoshi says, “but no mechanism exists to make payments over a communications channel without a trusted party.”

The solution? Peer-to-peer electronic cash. This breakthrough represents perhaps the most important development in economics since cowry shells and rai stones. Bitcoin enables us to make digital transactions without having to rely on credit. But, like cowry shells and rai stones, the system runs into some problems when we want to rely on credit.

Remember our friend the tailor. He was dealing with customers in person, but his ability to work on advance was central to his business. The merchants of the Mutual Communication Society speak to this reality: most economic and commercial activities rely on some notion credit.

Leverage, the borrowing that credit enables, is its own form of double-spending. Leverage is what exacerbated the 2008 financial crisis. But it is also what allows governments to borrow and fund their deficits, fueling economic growth. It lets us take out mortgages to buy our dream homes. It enables students to attend universities they otherwise couldn’t afford.

Credit is an integral part of any mature and functional economic system. So if cryptocurrency is digital cash, what does digital credit look like?

Pricing Risk

It’s important to remember that even outside the realm of cryptocurrency, our concepts of credit are always very messy.

Credit systems usually rely on attestations from a single authority, an oligopoly, or a web of trust.

If you want to extend a loan to me, you might check with my bank to see how much money I have and to learn about my historical patterns of earning and spending. In this case you would be relying on data attested by a single authority.

If you perform a formal credit check (in the United States), you will get a three digit number back from a small set of actors — namely Experian, Equifax, and Transunion. This oligopoly will use their data on me, aggregated across my various financial accounts, to score my creditworthiness. A similar system exists for corporations and countries which are rated by S&P, Fitch, and Moody’s.

Finally, you could take a web-of-trust approach. This would be akin to a Mutual Communication Society. You could ask friends of yours who have dealt with me in the past what they think. Have they loaned me money? Have I repaid them? Am I reliable?

No matter which of these approaches you take, however, you will still be taking on some risk when you make me that loan. To make the risk worth your while, you can ask me to pay interest. In other words, you can price the risk accordingly.

Credit is even more complicated in cryptocurrency systems. Because actors on most cryptocurrency networks can remain pseudonymous, information asymmetry is even higher than in conventional markets. In particular, this means that it is not so costly for bad actors to commit fraud. An exit scam occurs when a party takes out a loan and then takes the money and runs. In a pseudonymous system there are few reputational consequences, no deteriorating credit score. And for the lender there is no bankruptcy court, no recourse.

Does this make it impossible to price the risk of extending credit in a pseudonymous system? I would argue no. But in order to understand how there can reasonably be credit markets *~*on the blockchain*~* we will first need to dive into the topic of identity…

For more on the Mutual Communication Society, go read A Culture of Credit: Embedding Trust and Transparency in American Business by Rowena Olegario.